0xL4ugh Writeup: 'dance'

A writeup for a reversing challenge from the 0xL4ugh CTF involving runtime bytecode modification.

This is my solution for the “dance” crackme me which was created by Stoopid for the 0xL4ugh CTF 2024. You can find it on crackmes.one.

A first look

Running the binary it helpfully informs us that it requires a flag to be passed as a command line argument:

1

usage: ./dance <flag>

If we run it with just any flag it takes a while but then returns nop.

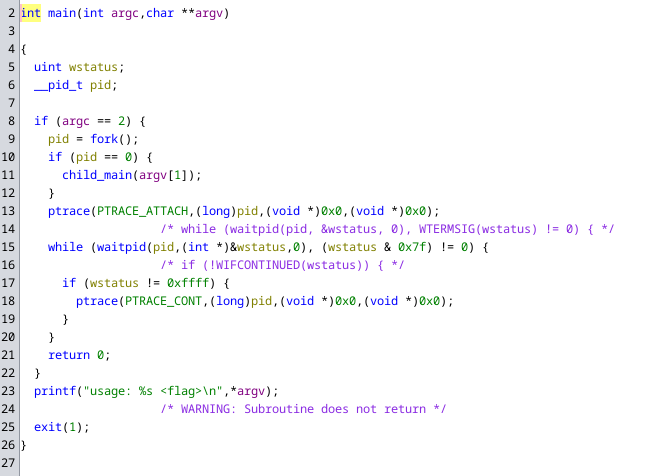

Taking a look at it in Ghidra, we can see that the following main function:

Besides printing the usage message, it forks the process and the parent process will then continue to monitor its child process, continuing it when it stops with an exit code that isn’t zero.

The behaviour of the child process is more interesting, it forks the process again and will then execute the following code in the new child process:

It seems to decrypt a large chunk of garbage data which is embedded in the binary and write it to a temporary file. Right after that it loads the temporary file as a shared library and executes the function int dance_with_me(char *flag) from it. Dependending on the result of the function call it will then print either “nop” or “ok”.

Extracting the second stage

From this it seems like the decrypted binary must contain the functionality for validating the flag. Using gdb we can simply set follow-fork-mode to child and set a breakpoint before the temporary file is loaded and copy it from /proc/<pid>/fd/3.

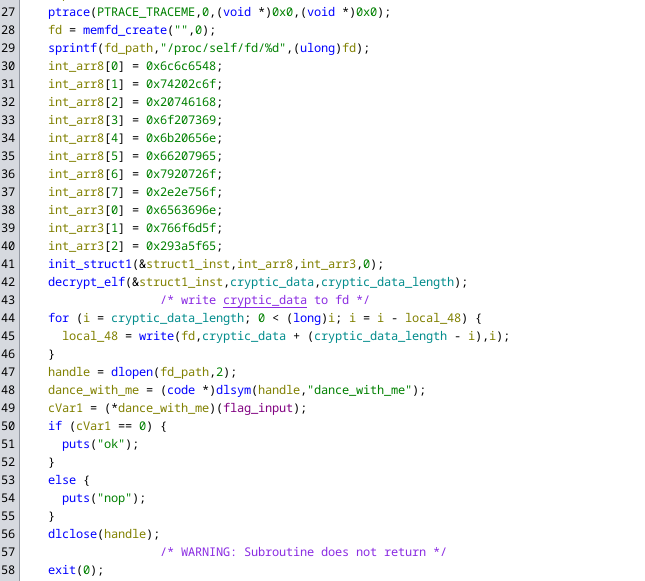

Looking at the dance_with_me function in Ghidra however we see this:

I don’t know about you, but this doesn’t look like normal code. Looking a bit closer it seems like the entire .text section of the binary only contains the one byte int3 instruction. Calling this instruction will cause a SIGTRAP signal to be sent to the parent process and the ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, ...) lets us know that the parent process is most likely catching these signals, so let’s take a look at what that process does with them.

Understanding the middle process

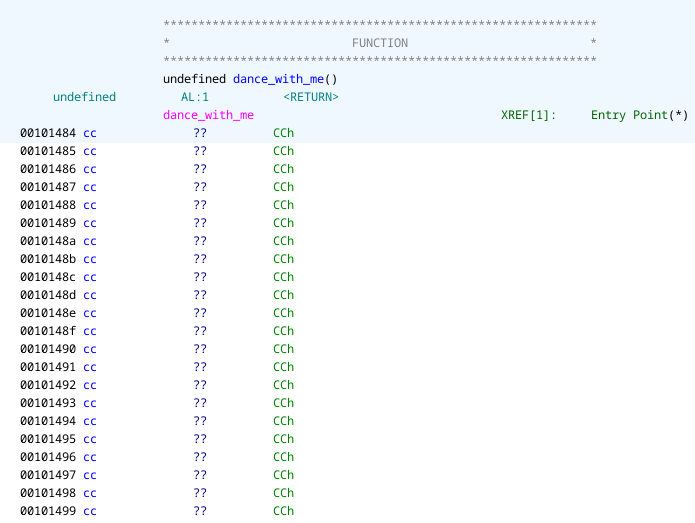

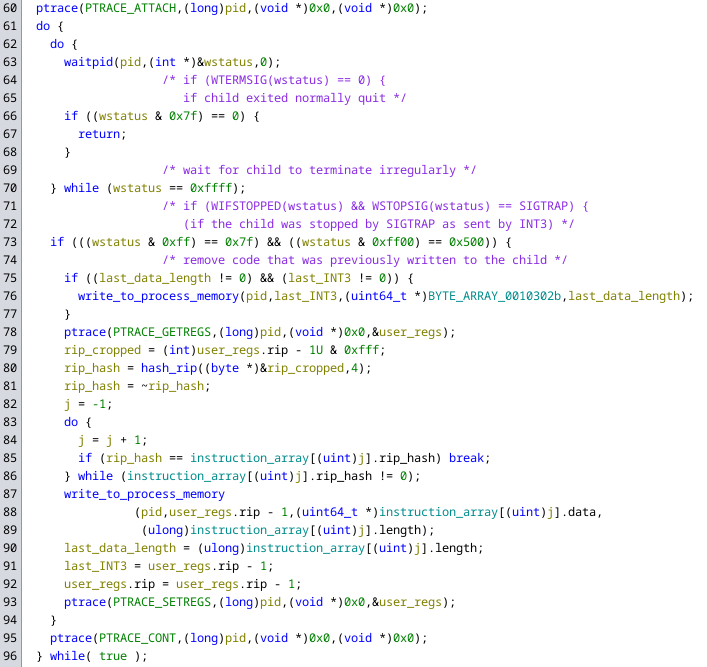

In ghidra we can see the following code for the middle process:

So we can already see ptrace calls that decrease the program counter by one, so when an int3 instruction is executed and this code is triggered the program counter will be moved back in front of the instruction.

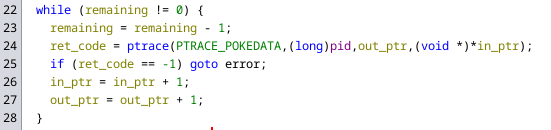

However we can also see that the program counter is not just decreased by one, but also transformed using some function, with the result being used to access some array. The resulting data is then passed to a function (which I have named write_to_process_memory) with the following code:

This code writes the supplied data into the memory of the child process eight bytes at a time. The rest of the code in the function (which is not shown above) just handles data that is not a multiple of eight in length.

The last thing we can see in the signal handling is that the location of the last write to the child process memory is saved and on the next write it will use this to remove the previously written data from the memory of the child process.

Bringing all of this together, we know that the middle process replaces the code of the child process during execution and removes it after it was executed.

This means that to analyse the flag verification process, we will first have to apply the patches done at runtime to the extracted binary of the second stage, so that we can then anaylse that in ghidra.

Populating the second stage

To achieve this I first reimplemented the function that transforms the program counter (which is called hash_rip in the screenshots above) like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

unsigned int *rip_translation = (unsigned int *)&rip_translation_char;

unsigned int hash_rip(uint8_t *rip_ptr, long length) {

long i;

uint8_t *input;

unsigned int outp;

outp = 0xffffffff;

input = rip_ptr;

for (i = length; i != 0; i--) {

outp = rip_translation[(*input ^ outp) & 0xFF] ^ outp >> 8;

input++;

}

return outp;

}

unsigned int rip2hash(uint64_t *rip) {

uint64_t rip_int = *rip;

unsigned int rip_cropped = (rip_int - 1) & 0xfff;

return ~hash_rip((uint8_t *)&rip_cropped, 4);

}

(rip_translation_char is the array used in the binary, copied from ghidra via ‘Copy Special’ as a C Array)

Here rip2hash represents the everything done to the value of the program counter when the signal is caught. This implementation is almost entirely a copy-paste-job from ghidra and was tested on multiple examples so it should work.

Next I implemented the lookup of program counter to data to be written into the memory of the child process:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

typedef struct {

unsigned int hash;

uint8_t length;

uint8_t data[19];

} instruction_data;

instruction_data *instructions_array = (instruction_data *)&instructions_bytes;

uint8_t *addr2instruction(const uint64_t addr, uint8_t *length) {

uint64_t rip = addr + 1;

unsigned int hash = rip2hash(&rip);

for (int i = 0; instructions_array[i].hash != 0; i++) {

if (instructions_array[i].hash != hash) continue;

*length = instructions_array[i].length;

return instructions_array[i].data;

}

return 0;

}

(instructions_bytes was copied from ghidra like rip_translation_char)

Note that the address is incremented by one like it would be after the int3 instruction at that location was executed.

With this I implemented a write_all function which takes an address, a path to the extracted .text section of an elf and the virtual base address of the .text section and overwrites all consecutive addresses that it can find data for:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

uint8_t write_addr(uint64_t addr, FILE *file, uint64_t base_addr) {

fseek(file, addr - base_addr, SEEK_SET);

uint8_t length = 0;

uint8_t *data = addr2instruction(addr, &length);

if (data) {

fwrite(data, length, 1, file);

for (size_t i = 0; i < length; i++) {

printf(" Byte: %x\n", data[i]);

}

}

return length;

}

void write_all(uint64_t addr, const char *path, uint64_t base_addr) {

FILE *file = fopen(path, "r+b");

if (file) {

// successfully opened file

uint8_t written;

while (true) {

written = write_addr(addr, file, base_addr);

if (written) {

printf("Wrote %d bytes to %#0x (off: %#0x)\n", written, addr, addr-base_addr);

addr += written;

} else

break;

}

fclose(file);

return;

}

printf("couldnt open file\n");

exit(1);

}

Using all of this I implemented a simple command line utility to populate the second stage:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

void extract_text_section(const char *elf_file_name, const char *section_file_name) {

const char cmd_template[] = "objcopy --dump-section .text=%s %s";

char *full_cmd = malloc(strlen(cmd_template)+strlen(elf_file_name)+strlen(section_file_name));

sprintf(full_cmd, cmd_template, section_file_name, elf_file_name);

system(full_cmd);

free(full_cmd);

}

void replace_text_section(const char *elf_file_name, const char *section_file_name) {

const char cmd_template[] = "objcopy --update-section .text=%s %s %s";

char *full_cmd = malloc(strlen(cmd_template)+strlen(section_file_name)+(strlen(elf_file_name)*2));

sprintf(full_cmd, cmd_template, section_file_name, elf_file_name, elf_file_name);

system(full_cmd);

free(full_cmd);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 4) {

printf("usage: %s <skeleton_elf> <address> <base address>\n", argv[0]);

printf("address and base address should either both include the ghidra offset or neither\n");

return 1;

}

uint64_t addr;

sscanf(argv[2], "%lx", &addr);

uint64_t base_addr;

sscanf(argv[3], "%lx", &base_addr);

const char temp_file_name[] = "input_elf.text";

// extract .text section

extract_text_section(argv[1], temp_file_name);

// populate it

write_all(addr, temp_file_name, base_addr);

// replace .text section with modified version

replace_text_section(argv[1], temp_file_name);

}

This uses objcopy to extract and replace the .text section of the ELF. One could also parse the ELF via C code (which I originally did), but this is much more complicated and turned out to be a waste of time.

Using this we can populate the binary with the following command: ./populate dance-stage2-skeleton 0x10a0 0x10a0. In this command 0x10a0 is the virtual base address of the .text section in memory, meaning it tries to populate the entire .text section. In this case this worked without problems because there was an entry for every byte of the .text section, but on different binaries it might be neccessary to run this multiple times with different addresses that weren’t populated before.

Analysing the populated second stage

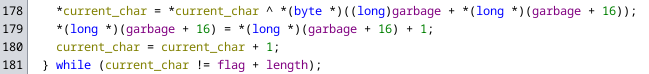

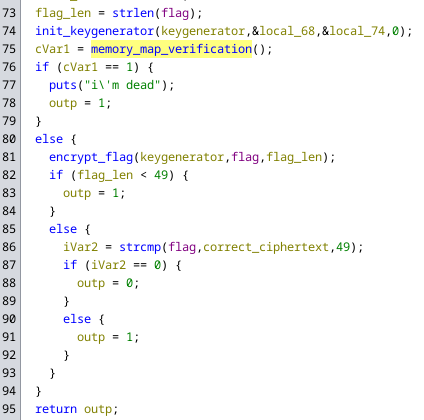

Loading the second stage into ghidra we see that the dance_with_me function references multiple other functions, how ever only two of them take in the flag, so let’s take a look at the first one:

In the screenshot you can see that the flag is iterated over character by character and each character is encrypted with bytes from a large buffer. The loop also contains more code which manipulates the data in this buffer, however since neither these manipulations nor the accesses use the flag it self and only depend on hard coded values, I didn’t look much closer into that part of the function and just assumed that it generates key bytes for the xor encryption independent of the input.

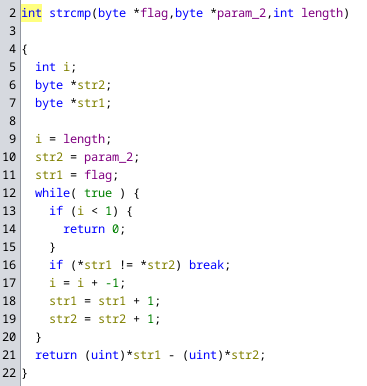

The other function that takes in the flag (after it was encrypted as described above) is this one:

Which can be easily recognized as an implementation of strcmp.

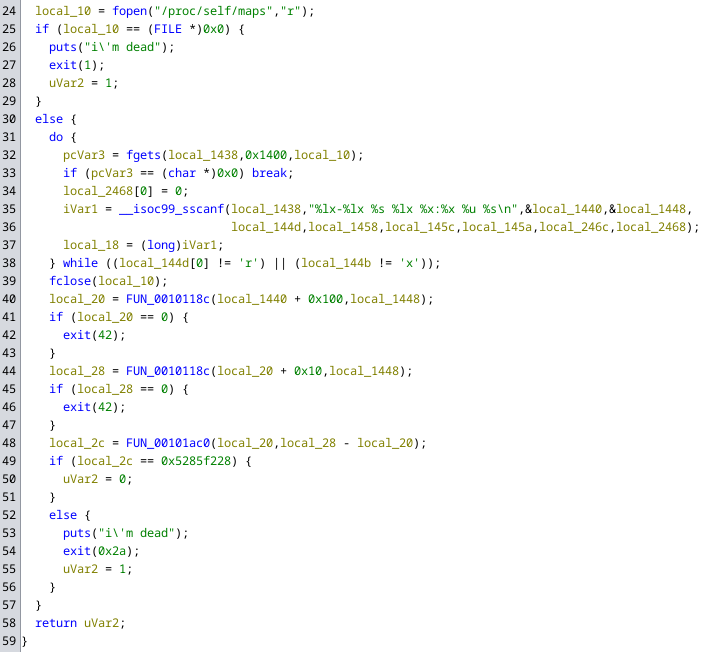

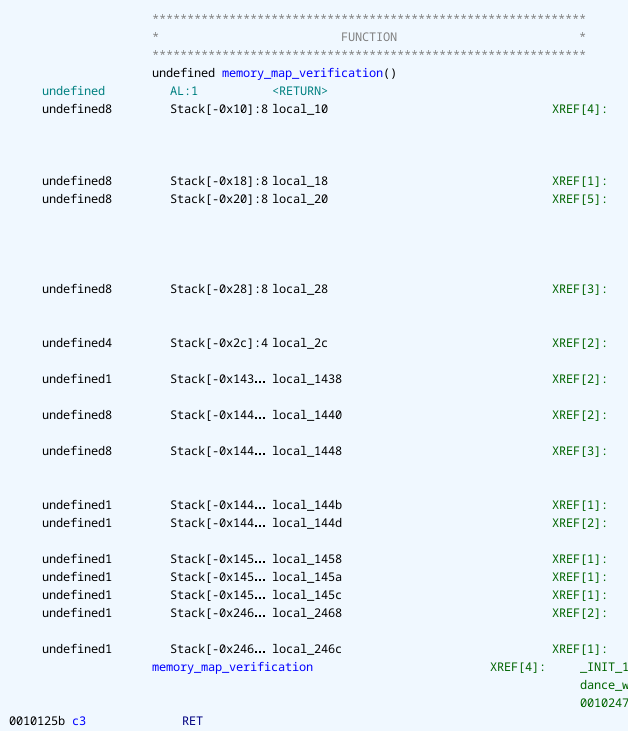

One other interesting function that I found looks like this:

It seems to validate the memory layout without actually affecting the verification of the flag in any way besides terminating the process if the verification fails.

Putting all of this together we get code for the dance_with_me function that looks like this:

Extracting the flag

Knowing that the flag is xor encrypted and the resulting ciphertext compared to a hard coded one, we should be able to run it with gdb and modify the arguments of the encryption to instead decrypt the hardcoded ciphertext. We can achieve this by replacing the flag argument of encrypt_flag with the expected ciphertext.

To do this we can simply write a program in C which loads the function and runs it, like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#include <stdio.h>

int dance_with_me(char *flag);

void main() {

dance_with_me("1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111");

}

However If we compile this and load it into gdb we get this:

1

cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

Ok this is a quick fix. Simply run export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$PWD which tells the dynamic linker where to find the shared object.

However running it now we still can’t debug it:

1

[Inferior 1 (process 8105) exited with code 052]

After way too much confusion on my end, I finally remembered that certain code from a shared object is executed when it is loaded. Knowing this we can look at the different init functions in ghidra and find this:

We already know memory_map_verification from earlier, it verifies the memory layout and terminates the process with exit code 42 if it is wrong. And as it turns out $0528 = 42{10}$ which is the exact return code that gdb was telling us about.

Knowing this we can simply patch the memory_map_verification to completely disable it:

Running it now we have no problems and can simply proceed as planned to get the flag: